Can Vietnam ease the semiconductor chip shortage?

The complex impact of Covid-19 on supply chains has been particularly acute in the semiconductor industry. From the fabs making the chips, and the factories testing and assembling them, to the industries which build their products around them, semiconductors illustrate how hard it is to manage supply chain bottlenecks in a crisis.

But there are glimmers of hope that the crisis may be easing. Take Vietnam, for example. A shift in policy and a mass vaccination program have helped get the production lines going again. The next step: adding alternative shipment services that get the chips to their destination to ease logjams downstream.

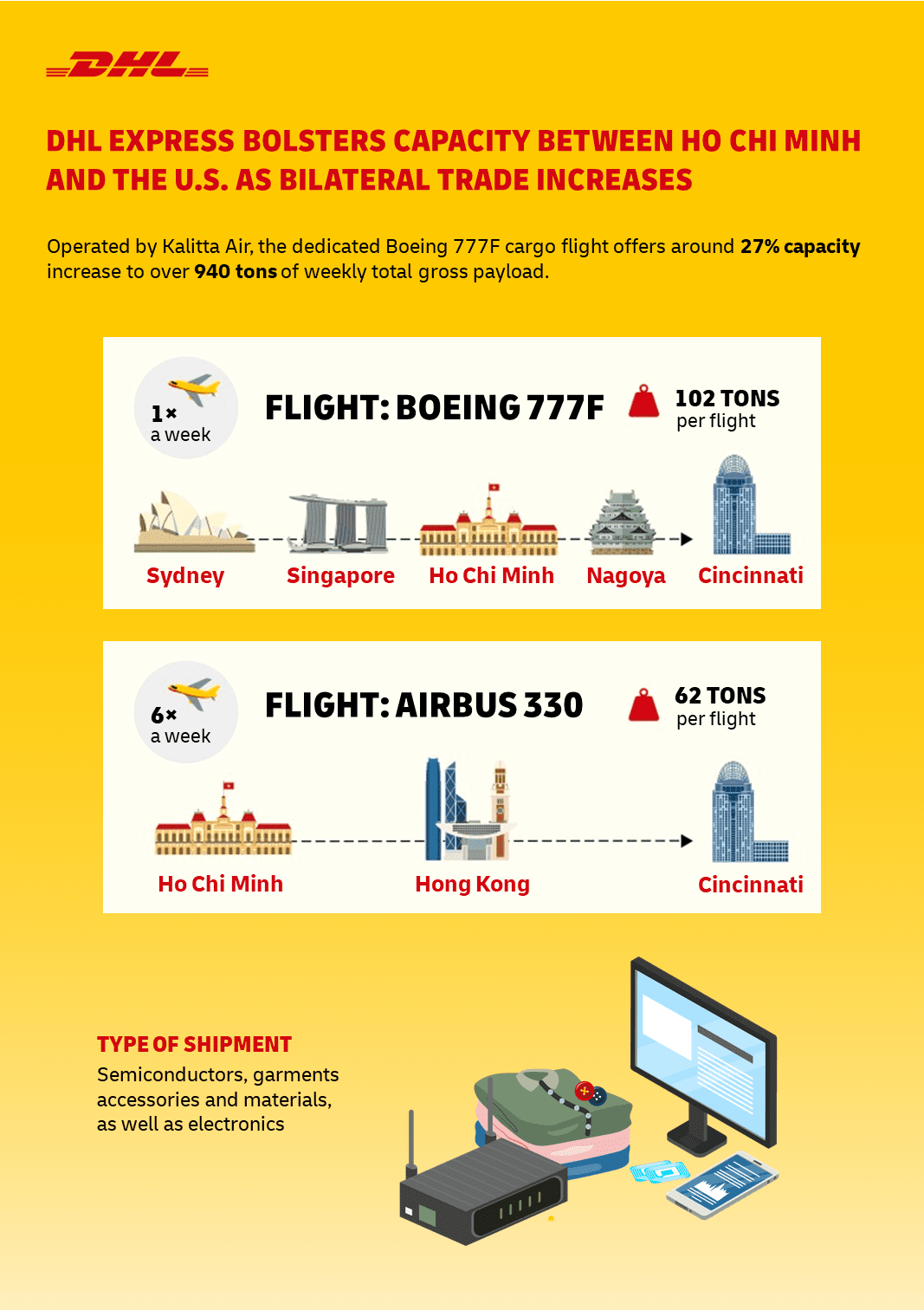

DHL Express, for example, has launched new weekly flights from Ho Chi Minh City to the U.S., which adds up to 102 tons of additional capacity, and is an alternative to the current flights that land in the U.S. via Hong Kong.

Vietnam’s story illustrates the challenges and opportunities of embedding a country into a key component in multiple industries.

The country has, in just a few years, emerged as a key part of the semiconductor ecosystem. In 2001 it ranked 47th in electronics exports; by 2019 it was 12th. It ranks second in smartphone exports, and has attracted major investments from Samsung, Intel, LG, Canon and Panasonic. As of April last year, Vietnam accounted for 30 percent of total semiconductor products imported into the US.

But all that has been threatened by a zero-Covid-19 policy that closed factories and were cited as a key reason for the delayed launch of Apple’s iPhone 13 in September 2021.

Rise of a global chip shortage

The pandemic has proved especially disruptive for the chipmaking sector, which in turn has severely impacted a swathe of other industries – affecting how quickly consumers can buy a new smartphone, replace a broken washing machine, or drive a car off the lot, for example.

Sales of electronic products requiring chip input components have skyrocketed, thanks to a boom in sales of work-from-home technology such as laptops and webcams, and home entertainment products like games consoles.

But outbreaks of Covid-19 in regions where the chips are made – especially the Asian powerhouses of Taiwan, China, Japan, and South Korea – have caused foundry closures that have left semiconductor makers struggling to keep up with demand.

Factory shutdowns have also impacted supply networks, leading to longer delivery times. The semiconductor supply chain is long and global, involving many specialized fields, so shortages created by operating restrictions in one region can lead to bottlenecks in others.

A lack of alternative supply networks and an ongoing scarcity of raw materials is only compounding the challenges chipmakers face.

The effects have been severe. For example, the U.S. government’s research found that many domestic manufacturers using semiconductors are now down to less than five days’ worth of chip inventory. Before the pandemic, companies typically maintained 40 days’ worth of inventory.

Chip prices have also risen, with consumers feeling the pinch. Prices of computers, tablets, and even smart televisions have soared by as much as 30 percent.

Vietnam’s diverse chip manufacturing competencies

More recently, the wave of Delta-driven infections across Southeast Asia in the second half of 2021 highlighted the critical role economies such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam play in the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain.

The country’s fast-emerging chipmaking sector is a major part of its thriving electronics industry, which in 2020 amounted to about 44 percent of total export volume.

Vietnam’s business-friendly government, expanding digital ecosystem, and fast-growing economy have helped the sector attract major foreign players. Samsung, Qualcomm, SK Hynix, and NXP Semiconductors are just a few of the multinational corporations that have built research centres and factories in the Southeast Asian country. These chipmakers have bolstered the country’s logistics infrastructure, which in turn has made it more appealing to other multinational firms.

A key differentiator for Vietnam’s chip sector is its strength in vital ‘backend’ operations such as cutting the processed silicon wafers into chips and subjecting them to a battery of tests before packaging and shipping them to customers.

Intel, the world’s largest integrated device manufacturer, has poured USD1.5 billion (€1.3 billion) into its Vietnamese chip assembly and testing plant since setting up shop there in 2006. In 2021, the corporation also committed to spending an additional USD 475 million to expand the plant.

Technology giant Amkor is building a state-of-the-art semiconductor packaging factory in Vietnam to enable it to take advantage of strong market demand in this specialized field.

Addressing the Covid-19 supply chain crunch

All these point to Vietnam’s importance in the semiconductor supply chain, but like its counterparts, it was not spared from the pandemic’s debilitating effects.

When the Covid-19 Delta variant erupted last year among a population that was almost entirely unvaccinated, Hanoi quickly responded with temporary business shutdowns and movement restrictions designed to keep the virus at bay.

By August, Vietnamese authorities were seeking other ways to address the outbreak, to enable factories and assembly plants across sectors to get back to full output and to help ensure products could reach their destinations on time.

Hanoi formally abandoned its zero-Covid-19 policy in September and ramped up its vaccination program. By early October, most factories had resumed normal operations and production levels were steadily picking up.

Today, with the adult vaccination level in Vietnam at around 90 percent, economists say the country is now far better prepared for any fresh waves of infection and poised for a return to growth.

“I don’t see further outbreaks posing as big a threat to Vietnam’s economy as Delta did last year, because it has better adapted to living with the virus,” Ruchir Desai, Fund Manager, Asia Frontier Capital, told Bloomberg in a recent news report. “In fact, I foresee a pretty strong recovery for Vietnam in 2022.”

Exports to drive return to growth

A report from Fitch Ratings also forecasts that Vietnam’s recovery is set to gather momentum in 2022, as domestic demand rebounds and export performance remains strong.

Meanwhile, the Asian Development Bank has kept its forecast for Vietnam’s GDP growth unchanged at 6.5 percent this year, adding that exports will continue to drive that growth.

With global demand for chips still buoyant, research is also suggesting that pandemic-related disruptions are unlikely to diminish the long-term potential of Vietnam’s semiconductor sector. Forecasts indicate that the industry will be worth US$6.16 billion by 2024.

A recent visit from U.S. Vice President Harris had its focus on finding ways to help Vietnam restore production and shore up supply chain resilience. This, in turn, has helped to galvanise optimism for Vietnam’s recovery.

“The visit of Vice President Harris has presented a positive signal for the recovery of semiconductor production in Vietnam, as well as attracting a new upcoming wave of large investment from chipmakers from the US,” Meir Tlebalde, Associate Director at KPMG Vietnam, recently told Vietnam Investment Review. “That could help minimise the level of the global chip shortage crisis impact in Vietnam.”

This has also translated to a strong growth in the demand for logistics services between U.S. and intra-Asia. “With Vietnam’s continued rise as a manufacturing hub for semiconductors, garments accessories and materials, and electronics, we see an increasing demand for our services and we are committed to support our customers in growing their global footprint and entering new markets,” said Ken Lee, CEO, DHL Express Asia Pacific.

Shoring up supply chain resilience

There’s still a way to go. A new U.S. government report is forecasting that the global chip shortage will persist until at least the second half of 2022, placing further strain on major industries, including consumer electronics and automotive, and potentially driving up prices.

On the capacity front, the disruption and loss of bellyhold and freighter capacity in China still remains a key obstacle” in the face of rising demand. In December 2021, overall schedule capacity was 17 percent lower when compared to the more meaningful comparison period of December 2019.

For countries like Vietnam, the challenge is to build a more resilient and competitive industry, which means, in part, to improve the logistics solutions available.

Exporters are looking for new ways to ensure that Vietnam-produced chips can get to their destinations quickly and seamlessly, and how producers can avoid the risks associated with delays or chokepoints.

The new weekly flights by DHL Express, which supplements its existing route between Ho Chi Minh City, Hong Kong and Cincinnati, provides an extra level of flexibility for exporters.

Besides Ho Chi Minh City, the route will pass through various cities, including Sydney, Singapore, and Nagoya before arriving at the DHL Express Cincinnati hub in the U.S. as its final destination. In total, 204 tons of additional capacity are created with the flight, bringing the weekly total gross payload to over 940 tons.

The increased payload reflects the imperative for logistics companies to continuously evaluate and respond to the market demand by adjusting its air network and dedicated freighters.

“Doing so will provide us with the necessary insights to improve our routes to perform efficient, time-definite international deliveries, despite the capacity crunch in the global supply chain,” said Sean Wall, Executive Vice President, Network Operations & Aviation, DHL Express Asia Pacific.

ALSO WORTH READING

English

English