Tasmanian salmon farmers find a novel way to get their catch to market

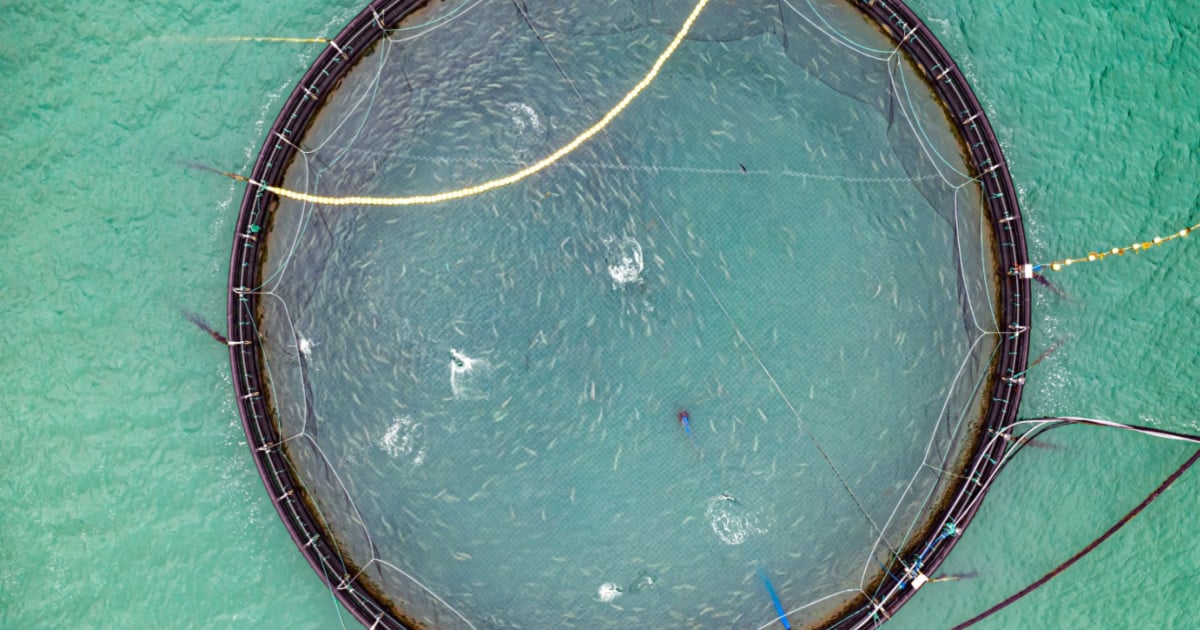

Salmon are reared in the seas south of Australia’s Tasmania for a reason: the waters are pure and free of diseases that commonly affect the anadromous fish, and warm enough to allow them to grow to a harvestable size within 18 months.

But what makes the location perfect for salmon also means it is far from any major shipping hubs. Getting them to market is a logistics challenge, even at the best of times. Covid-19 only made things harder, as soaring demand rubbed up against reduced shipping options — forcing the farmers and their local DHL partners to get creative.

The lesson to draw: beneath every robust logistics network lies a bedrock of adaptivity, creativity, and a willingness to collaborate to get the job done.

Background of Tasmanian salmon production

Since the 1980s, when salmon farming started in Tasmania, the global salmon industry was one of the fastest evolving food production systems in the world. Aquaculture – farming in water – is predominantly responsible for salmonid production worldwide, trumping wild-catch production and constituting 69 percent of global supply as of 2018.

Today, global salmon consumption makes up a whopping 70 percent (2.5 million metric tons) of the growing food production market, having risen threefold compared to 30 years ago.

In Australia, salmon farms nestled along the blue coastlines of Tasmania contribute over 90 percent of the country’s salmonid production.

Moving Tassie salmon around

The nature of salmon as a highly perishable product means that issues such as time and temperature are crucial in logistics, and manufacturers often freeze them before they are shipped to slow the growth of harmful microorganisms.

When salmon are improperly stored or transported, however, they can quickly deteriorate, leading to premature losses during the shipping process.

Tasmanian salmon must embark on a long journey from the very southern tip of the island to the north before they can be distributed to key domestic and international markets.

There, barges take the salmon across the Bass Strait to mainland Australia. Using a combination of sea and road freight, the fish are then shipped to gateway ports in Melbourne and Sydney, and transported to their respective markets. This logistics process takes 24 hours and leaves little room for error.

For instance, salmon must be kept at constant temperatures and in protected packaging to prevent spoilage. Carriers must also be wary of unforeseen events like delayed custom processes and port holdups – both of which can risk the freshness of such perishables in transit.

Tough competition

Six years ago, Australian salmon production was still very much seasonal, clocking the largest export volumes during peak months from August to January. The problem, however, was that there would be virtually no exports for the rest of the year, as time is needed for their fish to grow bigger again.

In comparison, one of Australia’s biggest competitors in the salmon industry, Norway, had seen signs of salmon farming from as early as the 1970s. This was kickstarted by the Grøntvedt brothers from a small island named Hitra, who decided to capitalize on a declining salmon population and capture wild salmon using floating net pens.

With a regular diet and protection from their natural predators, the fish in the pens flourished, and the siblings quickly realized the profitability of rearing salmon in well-treated enclosures.

Thanks to their experience in salmon production, Norway today owns a more well-developed farming infrastructure to produce salmon throughout the year. That presents yet another challenge for Australia to keep up with their competitor in getting fish to market worldwide.

Despite this, Australian salmon producers have made notable strides in emulating the Norwegian model for the past 10 years, getting close to maintaining a consistent supply of salmon all-year round.

“Aussie salmon seasonality has gone from say, you know, a six- to seven-month hiatus down to basically three to four, and then probably over the next five to six years that will just continue to reduce as their production increases,” said Bernie Cooney, Perishables and Livestock Manager, DHL Global Forwarding Australia.

Salmon popularity amidst Covid-19

In recent years, Tasmanian salmon have found their way onto dinner tables around the globe, owing to several factors such as an increasing awareness of their health benefits, as well as a shift in people’s consumption patterns. In fact, Tasmania’s booming salmonid aquaculture sector holds most of the seafood and aquaculture workforce in the resource-laden island.

Yet, even with the steady climb in salmon production, the quality of Tasmanian salmon has never been a trade-off for the farmers who take pride in delivering the freshest product, regardless of the challenges they face logistically.

Originally, frozen salmon went mostly by ocean freight, whereas fresh fish were transported in the air. However, Covid-19 exacerbated challenges like port congestion, forcing many farmers to freeze their products because fresh fish could not reach their markets in time.

In addition, a severe lack of flight capacity out of Australia meant that most of the salmon had to be transported to specific airports hundreds of kilometers away for delivery, particularly to Sydney where most of the flight capacity remained. This process added to the woes of getting Tassie salmon to international customers during the pandemic.

The message was clear for Tassie fisheries and for logistics provider DHL: it was time to get creative and work together in exploring their options.

No rocks unturned

DHL tapped into its network and identified several carriers they could join forces with. Because Australia still had a lot of import and export demand, DHL wanted any new flights chartered into the country to operate as efficiently as possible – not flying solely for salmon, but other cargo as well.

“Instead of looking at it as a one-way charter opportunity, we started to think: what can we do with round trips?” Cooney said.

To ensure smoother air freight operations, DHL collaborated with partner networks on round-trip routes that would bring imports in and charter exports out of Australia.

Aircraft carrying foods from Europe and the U.S. to Hong Kong were first chartered down to Sydney where they were loaded with salmon and general cargo. They were then chartered back north, delivering to key markets like Shanghai.

To charter its general cargo out of China down to Australia, DHL engaged a partner network that had existing routes from Brisbane up to Taipei. The route would fly general cargo out of Shanghai down to Brisbane, before making a round trip back to Taipei.

The operation reinvigorated Australian pipelines and enabled flights from DHL's partner network to start flying in and out of Australia again amidst reduced flight capacities.

It also came as a saving grace for salmon exporters, as it was much cheaper to channel different cargo onto aircraft making round trips to key markets.

Since then, DHL has further collaborated with its partner network on other routes today for general cargo, typically out of Brisbane.

Promising signs

Normally, Norwegian salmon would be priced below Australia’s because of the sheer volume of salmon they can produce. However, the additional costs loaded onto the Norwegian product due to the Covid-19 lockdowns in China and the Ukraine-Russia conflict have driven up Norwegian salmon prices.

This has closed the price gap between Australian and Norwegian salmon and, in turn, helped keep Australian salmon competitive. For now, the low harvesting season has made things slightly quieter again for the Australian salmon industry, as there are fewer salmon ready for sale at a harvestable size.

Although the aftermath of Covid-19 on travel and freightage has yet to subside, Cooney says that a more stable outlook may be on the horizon for flight capacities, as compared to just before the pandemic hit.

“There were 2,000 flights out of Australia pre-Covid, and I think as of June, there were about 940 flights,” Cooney said. “So, we’ve certainly come a long way from the 300 flights when Covid-19 first began.”

For Cooney, the lesson has been a simple one: “You need to be able to think on your feet and always look outside of the square,” Cooney emphasized. “Because if you don’t, somebody else will.”

ALSO WORTH READING

English

English