Australia’s maverick mindset to finding its future in the dairy industry

Dairy is one of the most important agricultural industries in Australia. Valued at US$3 billion, it plays a key role in rural employment and food supply. While the country accounts for less than 2 percent of the world’s milk production, it is the world’s fourth-largest dairy exporter.

But a dairy farmer’s job is no easy feat, in part due to a shrinking market and high labor costs. Since the Australian government deregulated the dairy market in 2001, Australia’s milk production has dropped off.

Still, Australia’s position is unique, as falling domestic demand is countering the slowdown in production. The industry has also maintained a steady growth rate by producing value-added milk byproducts.

“The dairy industry is becoming tougher to carve a living out of, ” said Bernie Cooney, National Perishable and Livestock Manager, DHL Global Forwarding Australia, “That’s why producers are diversifying production and focusing on popular products to keep up with trends.”

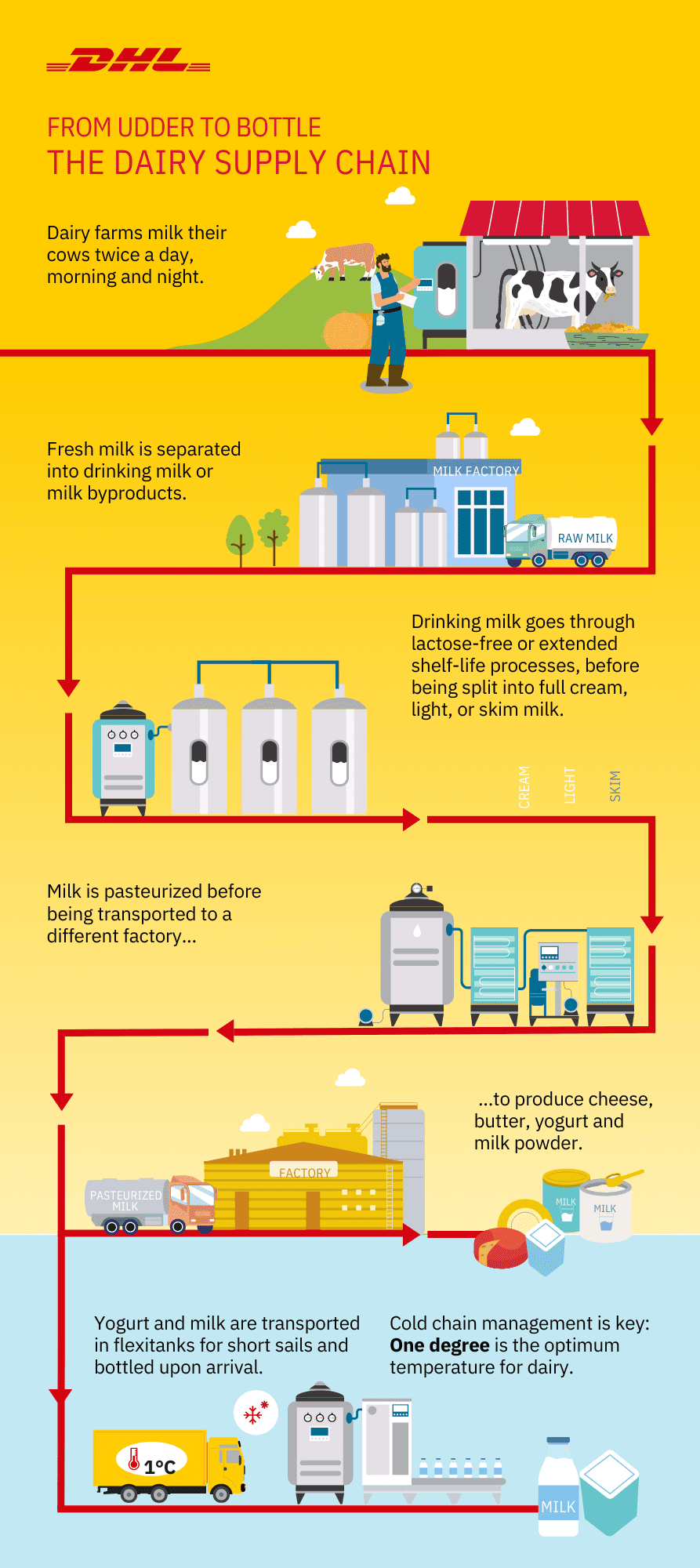

The complex network from udder to bottle

Beginning from the milking parlors, the dairy supply chain is a diverse network that stretches into several processes in different factories. Dairy farms milk their cows twice a day, morning and night. The fresh milk is collected, then separated in the production facility for either consumption or the production of milk byproducts, and transported to processing facilities in non-refrigerated tanker trucks.

The milk gets broken down into categories such as fresh, full cream, light, or skim milk. It is then treated accordingly with lactose-free or extended shelf-life processes, which take about five to eight days.

Factories with separate production lines for milk byproducts start by processing fresh milk and refining it through processes such as pasteurization. After which, the milk is transported to a different factory to produce cheese, butter, and yogurt.

Another popular product is milk powder. 3 percent of Australia’s fresh milk is processed and freeze-dried into milk powder. These are packed into 2kg and 20kg bags for retail and commercial use respectively.

Products with longer shelf life, such as yogurt, are transported via ocean freight in flexitanks, while fresh milk is often transported via air freight. In cases where the destination country is a short sail away, milk is transported via flexitanks. Milk from Fremantle, for example, is sent on a four-day sail to Singapore and bottled upon arrival.

During transit, temperature fluctuation must be kept as low as possible, even during transit with the defrost cycles of the refrigeration unit.

“When it comes to dairy and particularly fresh milk, cold chain management is key,” said Cooney. “They need to be refrigerated between one to three degrees, with one degree being the optimum temperature.”

As such, bottled milk is generally packed tightly in cardboard boxes, made to be dense and heavy to maintain its temperature throughout the course.

The Australian dairy farmer’s challenges

Australia’s dairy market is scarcely self-sufficient, with only 36 percent of milk being exported. Meanwhile, dairy production has declined over the past decade. A report by Rabobang in August 2022 indicated a sixth consecutive year of decline in the total volume of milk produced in Australia.

“Milk producers are struggling to get enough milk to meet the demand for milk-based products such as yogurts, cheeses, and creams, not only for domestic consumption but for export as well,” noted Cooney.

Amid the decline in supply, the cost of production has risen, with labor costs skyrocketing, pushing prices so high that some of the importing markets cannot afford to pay for Australian milk.

“To curb the issue of high labor costs, many farmers have invested in automated equipment for the milking process in their harvesting blocks to create a more efficient workflow,” noted Cooney.

Milk prices and all dairy is worth

Inflated freight costs during the Covid-19 lockdown also resulted in a major challenge for Australia. Its biggest importer, China, could not afford to ship milk powder regularly via air freight.

Fortunately, Chinese retailers adapted quickly, opting for bulk shipments via ocean freight. Micro-fulfillment warehouses were also set up in China to distribute stock on demand. The distribution hubs helped to keep a steady demand for milk powder from Australia in China, bringing much relief to Australia’s dairy market.

Back in Australia, low domestic returns are a massive challenge for dairy farmers. A price war between dairy retailers in Australia pushed milk prices to hit as low as AU$1 per liter, limiting the returns that farmers got for their milk.

The situation improved when the Dairy Council of Australia stepped in, encouraging consumers to buy from brands with higher returns to the farmer. The change in consumers’ mindset and purchasing behavior pressured the dollar-a-liter milk retailers. Eventually, the retailers raised prices to reasonable levels, and thus increased returns for dairy farmers.

To top it off, Australia has a strong competitor from its neighbor, New Zealand, whose dairy market is thriving due to strong government regulation. Its plentiful rainfall leading to greener pastures for dairy production is a stark contrast to Australia’s years of drought.

“Producers are leaving the market because they can’t make the returns on their investments work,” said Cooney, noting that the profit margin for Australian milk is almost three times lower than New Zealand’s.

As such, the regions that Australian dairy farms are based in have been shrinking into coastal areas. This includes the Southeast of Victoria, and Southwest of Western Australia, where there are higher percentages of rainfall.

Adapting to the future of Australian dairy

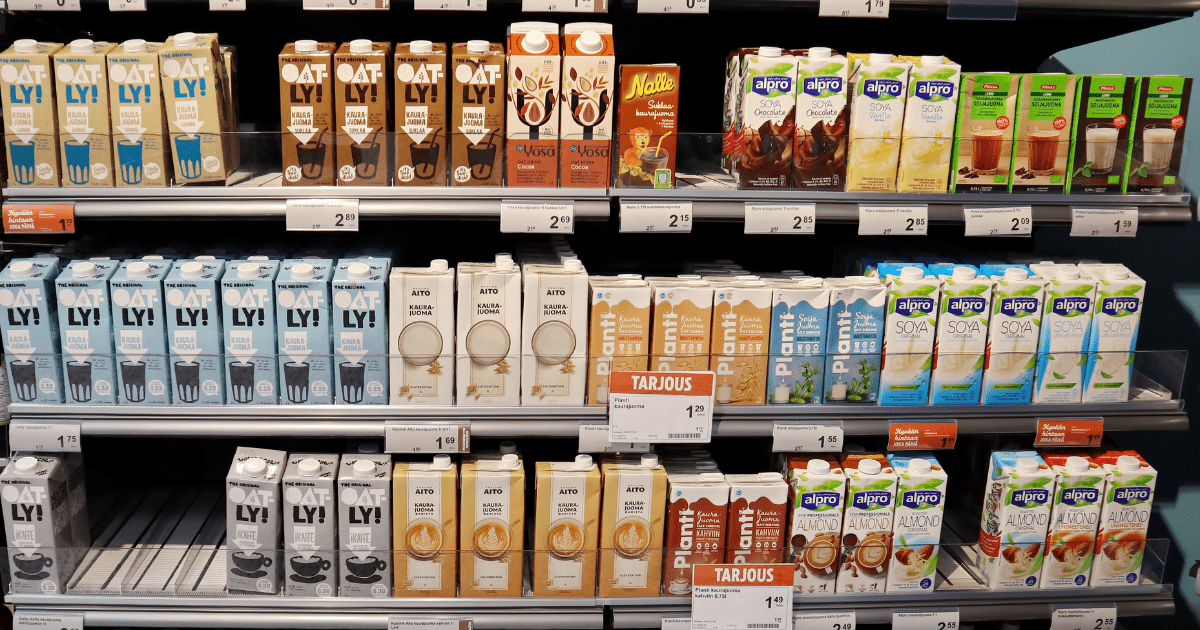

Amid a decline in the country’s milk production and demand for cow’s milk, there is a rising demand for plant-based milk. In 2022, only 30 percent of the milk produced in Australia was consumed domestically. That number is quickly declining as consumers, opting for a healthier lifestyle during the pandemic, are switching to plant-based milk.

“Soy milk and almond milk are growing very popular because they’re being touted as the alternatives to cow's milk for people who are lactose-intolerant or allergic to animal-based dairy,” observed Cooney. “Many milk producers in Australia now produce a wide range of not just traditional full cream milk, but lactose-free, non-fat, skim, and A2 milk, where the A1 protein is removed.”

Besides the rising demand for plant-based milk, milk byproducts, such as cheese, and cream, are increasing in popularity too. 40 percent of Australia-produced milk is used to make cheese, while another 30 percent is used to produce other value-added products like butter, milk powder, and yogurt.

“Since the demand for fresh milk is low, producers are more targeted in terms of what they sell,” noted Cooney. “Particularly in Victoria and Tasmania, we have a lot more boutique creameries being set up.”

Cooney is hopeful for the dairy industry’s progress in the long run. Apart from adapting to market trends, Australian farmers are also looking for more sustainable ways of production where they can reduce their carbon footprint. From solar batteries to automated processes, farms are moving away from relying on the electricity grid.

“Innovation and keeping an open mind are necessary to adapt to the market trends, and Australian dairy farmers have proven that they are capable of that,” noted Cooney.

ALSO WORTH READING

English

English